Every now and then there’s talk of an ETF ‘bubble,’ Which results in audible groans from the ETF and index investing industry. It’s no coincidence that those most threatened by ETFs and index investing (active managers) are also its most vocal opponents.

This isn’t new.

The active funds management industry has rallied against index investing ever since the first index fund was launched in the 1970s.

Despite this, S&P Dow Jones estimates that indexing has saved investors US$320 billion in fees since 1996.

In this article I’ll explain:

- What led me to index investing

- Why active investors play a vital role in the market (and why you should avoid them!).

Finally, I’ll dismantle seven popular myths pedalled by active fund managers about indexing and ETFs.

Part 1: What led me to index investing

My background is not what you’d expect for a strong advocate of index investing. I was an active investor since buying my first share at the age of 11.

I was fortunate to be mentored by some truly brilliant investors and traders during my career. However, working in the funds management industry made something very clear to me.

Firstly, the vast majority of fund managers do not beat the market after their fees are subtracted.

Picking winners in either individual stocks or in fund managers is difficult for the same reason: beating the market is a zero sum game, meaning for every winner there’s a loser.

Because all active fund managers charge significant fees, it’s a mathematical certainty that as a group they must underperform the market. Fewer than 15% of Australian share market fund managers beat the market over 15 years.

The results are even worse for global fund managers with less than 7% beating the market. For other asset classes, like Australian bonds, only 17% of managers beat the market after costs.

In 2019 paper, the Pensions Institute compared 516 active share market funds over 10 years and found that only 1% of active funds were able to produce enough returns to offset their costs.

Incredibly, 99% delivered no outperformance after costs. The report also found that it’s “incredible hard to identify” which fund managers are going to do well in the future.

One reason for this is that active fund managers who do well in one period tend to do poorly in the next. It takes 22 years of performance data to be 90% confident a fund managers’ performance is actually due to skill and not luck.

In reality, only a tiny percentage of investors consistently beat the market and they fall into one of two groups:

- they don’t need your money to invest because they’re already independently wealthy from their skill; or

- they’ll take your money, charge a management fee and reward themselves for any outperformance.

All of this is why you are better off earning the market return through an indexed fund or ETF.

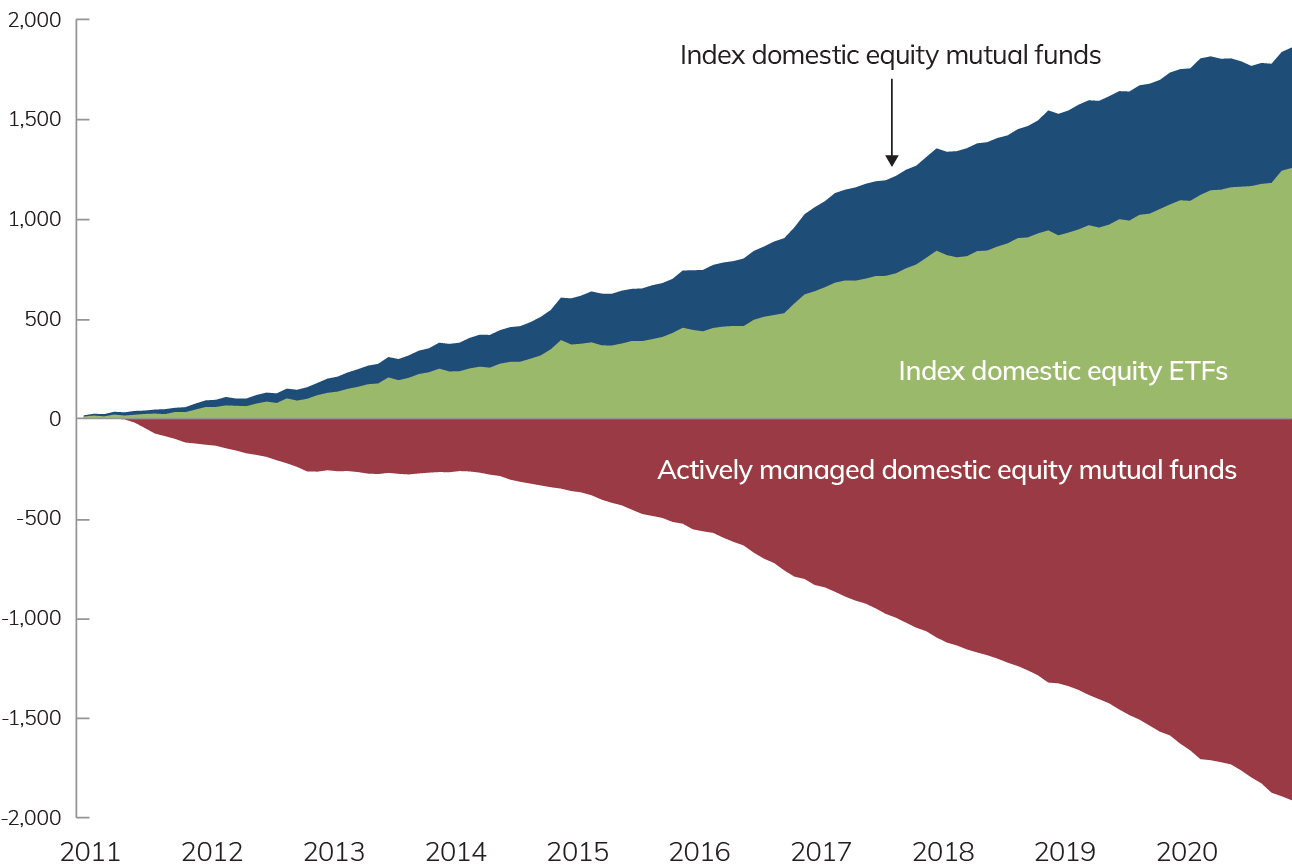

The trend out of active funds has been accelerating since the Global Financial Crisis when they provided no protection from the financial bloodbath.

Contributing to the trend out of active funds is regulatory change in recent years that requires advisers to act in the best interests of their clients. The other contributing factor is awareness of the benefits of low-cost investing.

Currently the 200+ ETFs on the ASX have a market capitalisation of over $100 billion.

In the US, ETFs comprise 18% of the investment fund market while in Canada and Europe they equate to over 10% of the total market.

Source: Investment Company Institute

Australians have saved almost $500 million in fees per year compared to investing through expensive and underperforming actively managed funds.

They continue to grow in popularity because they are a convenient and transparent way to invest into a large range of shares and because most fund managers can’t justify their fees.

Learn more:

Part 2: What’s the role of active fund managers?

Active fund managers do perform a vital role in setting the price of shares because they participate in almost all market trades and determine prices. This means that one active fund manager sells to another.

If the share price goes up, the buyer outperforms the seller. If the share price falls the seller outperforms the buyer. In practice, the seller is taking a bet that the price of the shares that he sells will not perform as well as the shares he has just bought.

For every active winner there has to be an active loser. There are thousands of active investors engaged in this every day – and the sum of their efforts amounts to the market price of each share and the market index level.

An indexed fund or ETF doesn’t buy and sell any shares in response to a fund managers’ opinion about future prices or dividends. Instead it owns all of the securities within an index.

The performance of the index fund is therefore the performance of the market as a whole. When you invest in an index fund you’re letting other informed investors set the fair price level – and you benefit from investing at that price.

As more money goes into indexing it becomes harder to beat the market because the less capable active fund managers are being weeded out.

Think of it like buying avocados at Woolworths. Behind the scenes informed people are setting the equilibrium price level. When you walk into the store you don’t need to ‘bid’ for an avocado, you just get the ‘market price’.

Index investors do need active investors to set market prices. But as an investor you don’t need to pay a high fee to the people setting prices when you can simply take the price they’ve set for a much lower fee.

This is the beauty of indexing.

Part 3: Demolishing a few myths about indexing and ETFs

Here are seven common myths peddled about ETFs and indexing and why they’re wrong.

Myth 1: Indexing makes all shares move together

ETFs do not pick stocks and therefore cannot set prices. Rather, they buy the companies within an index at their relative ‘market weights’. They have no influence over what shares come in or out of an index. All of that is determined by active buyers and sellers.

In any given year, one share within the index falls 20% while another share rises 30%. Money coming into index funds would buy both of these shares in their relative index weights set by active investors.

ETFs don’t actively buy and sell, so they only contribute a small amount of the overall trading volume. In most of the world it’s less than 10% of volume, and even in the U.S, trading by indexed funds only accounts for around 25% of volume.

Myth 2: Indexing misprices shares

This rumour seems to originate from fund managers who have underperformed and looking to excuse their poor performance. Index funds cop the blame for causing the shares they own to be ignored and undervalued.

ETFs cannot influence prices in any meaningful way. Furthermore, if indexing did cause shares to be mispriced this would create opportunities for active investors to beat the market. Active fund managers would be celebrating, not bemoaning indexing.

The more money that gets indexed, the less ‘dumb’ money is left for active fund managers to beat. This is known as the paradox of skill.

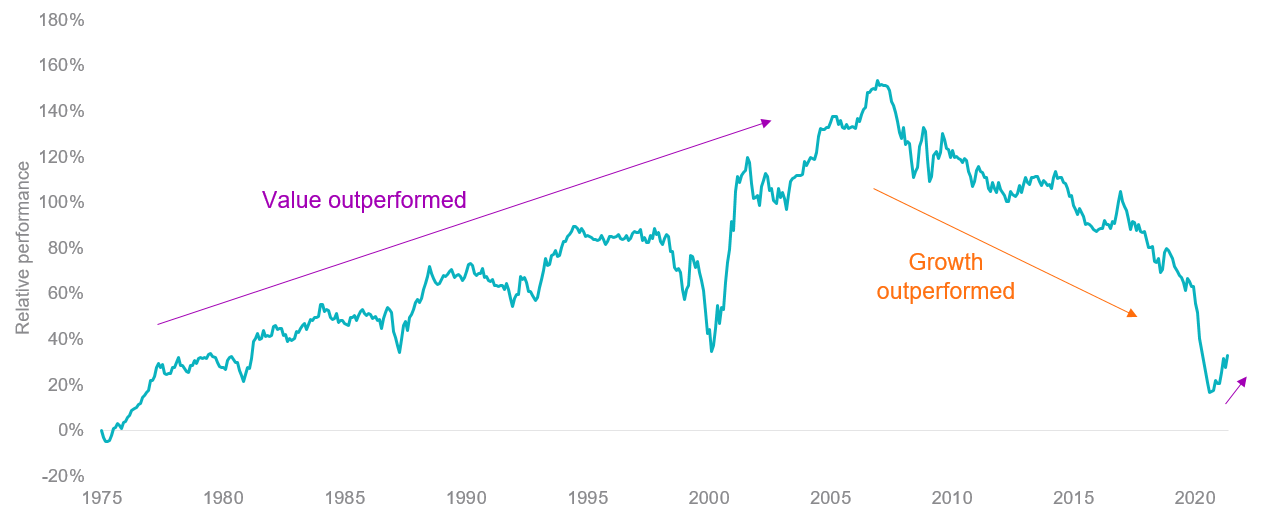

Myth 3: Indexing has harmed returns from ‘value’ shares and ‘small company’ shares

Throughout history there have been many periods where small companies have done better or worse than large companies, and when value shares have done better or worse than growth shares.

This has nothing to do with indexing and everything to do with normal market cycles. Sometimes, ‘value’ shares do well, sometimes ‘growth’ shares do well. It’s hard to profit from this because nobody really knows why, how long it will last or when the paradigm is about to flip.

Source: VanEck

A more likely reason value fund managers have done poorly over the last 10 years is too many value fund managers! Warren Buffett’s right hand man, Charlie Munger, says it best:

[Value fund managers] are “like a bunch of cod fishermen after all the cod’s been overfished. They don’t catch a lot of cod, but they keep on fishing in the same waters. That’s what’s happened to all these value investors. Maybe they should move to where the fish are.”

Charlie Munger

Myth 4: Indexing is a bubble – or is causing a market bubble

Booms and busts are not caused by indexing, it’s the herd mentality of investors chasing or leaving markets. Markets have gone through booms and busts since the start of time due to economics, governments, wars, monetary policy and a whole host of other factors.

There have always been sectors of the share market which have shown incredible volatility. In the 1630s it was the Dutch Tulip mania. In 1720 the South Sea bubble, and in the 1970s there was the infamous minerals boom led by Poseidon in Australia. 1999 was the year of the largest flow of funds into US tech shares ever. This was well before the growth of ETFs, yet there was no shortage of active fund managers eager to buy tech stocks at the peak.

At Stockspot we believe the safest way to avoid the risk of falling into the herd mentality trap is to provide a portfolio that has a balance between assets, countries and sectors.

We are wary of sector bubbles and allocate funds to safe havens such as gold to smooth returns. This, and our much lower fees, are the main reasons why our portfolios have outperformed more than 90% of similar investment funds over the last five years.

Myth 5: Active funds protect you in down markets

In the market falls of 2000 and 2008 active managers performed on par with the index. Jason Zweig provides an historical appraisal in Sorry stock pickers, history shows you underperform in down markets too.

The reason for this is that for every active investor who beats the market, there’s one who hasn’t. Active investing is a zero sum game versus the index.

Investors in actively managed funds are in aggregate certain to underperform the market by the fees charged by these funds in both up and down markets because active investors are the market.

As more money goes into indexing it becomes harder to beat the market because the less capable active fund managers are being weeded out.

Learn more:

Myth 6: Indexing could cause everyone to sprint for the exit when markets are stressed

Human nature applies equally to active and index funds. If more people want to sell than buy, both active and index investors are impacted equally. In any event, indexed funds still only comprise less than 3% of the Australian share market.

Even in the U.S., ETFs still only make up a small amount of the overall market and are much better equipped to handle situations where a lot of investors want to sell at once, whereas ‘closed’ active funds may ‘lock up’ investor funds.

An example of this is the active Woodford Equity Income Fund in the UK. Once a star fund manager it went in to administration and froze redemptions (sales). Investors in this fund weren’t able to get their money out when this happened.

Myth 7: Indexing is the idiot’s way of investing

A stockbroker recently told me that ‘buy and hold indexing is dumb’ and their clients were much more sophisticated because they ‘traded often’. However, an active investor trades on the assumption they’re better informed than other participants. An ETF investor benefits from the prices determined by active investors who are taking bets against each other.

Investing is one of the few places in life where the evidence shows that the more you do, the less you get.

For 30 years the DALBAR research has shown that people who make fewer decisions, both advised and unadvised, earn higher returns.

The truly sophisticated clients are the ones investing into index funds and doing nothing else.

The upshot of all this

It’s strange that some people think it’s a bad thing that people are moving money out of active funds that have high costs, high turnover, poor performance and are tax inefficient.

Indexing is none of these things and is also easier to understand and more transparent.

The rapid growth of index investing and ETFs over the past decade is here to stay and reflects the ‘deflating’ of the active investing boom of the 1980s to early 2000s.

Investors have rightly given up on the ‘star’ power of active fund managers.

I believe financial advisers should stop trying to pick whether prices are ‘too high’ or ‘too low’ (where they have no edge) and instead encourage clients to be disciplined to their investing plans and to stick with them.

For those who rely on active stock picking for their careers and businesses, indexing remains the easy punching bag because livelihoods are at stake. This raises some ethical questions around whether self-serving arguments are being put ahead of investors and clients.

Meanwhile there is one group you won’t hear complain about low-cost index funds and ETFs – the people who invest in them.