Super funds and other investment products like managed funds use ratings on their websites and marketing materials to attract customers as well as encourage financial planners to recommend them. In fact, many planners aren’t allowed to recommend a fund unless it has been professionally rated.

So what do fund ratings really mean and how useful are they?

What are fund ratings?

Ratings usually rank funds from ‘top’ to ‘bottom’ based on a set of criteria that have been chosen by a ratings agency. The major agencies in Australia are Morningstar, Zenith, Chant West, Lonsec, Super Ratings, Canstar and Mercer. Each has a different ratings structure based on what they have determined makes a good investment.

For instance, Super Ratings says their “methodology has been designed to reflect each funds ‘Value for money’”. To come up with this score, Super Ratings places about 45% importance on fees and performance, and 55% importance on other factors like administration, advice and governance.

| Assessment criteria | Weighting |

| Investment including: methodology, performance, risk profiles and process | 22.5% |

| Fees & Charges including: cost, structure & transparency over various account balance & employer sizes | 22.5% |

| Administration including: structure, service standards, internet facilities, employer and adviser servicing | 10.0% |

| Advice including: members education and financial planning | 10.0% |

| Governance including: trustee structure, processes & risk management | 10.0% |

| Insurance including: rates, options, terms & conditions | 10.0% |

| Qualitative Overlay including: overall benefts, fexibility & choice, transparency & usability | 15.0% |

Source: SuperRatings – Methodology Info Sheet

So do better ratings translate into better fund performance, better fund governance and better risk management? To answer that question it’s first important to understand how ratings agencies operate.

How do ratings work?

Most ratings agencies advertise themselves as being ‘fiercely independent’. For the most part this is fair, however ratings agencies aren’t charitable organisations so typically make money in one of three ways:

- Charge each super or investment fund a fee to be rated (e.g. Super Ratings and Zenith); or

- Charge each fund a licensing fee to use their ratings logos in their marketing materials (e.g. Morningstar’s stars); or

- Running an industry database for which funds must pay to be listed in, and only rating the funds listed in that database.

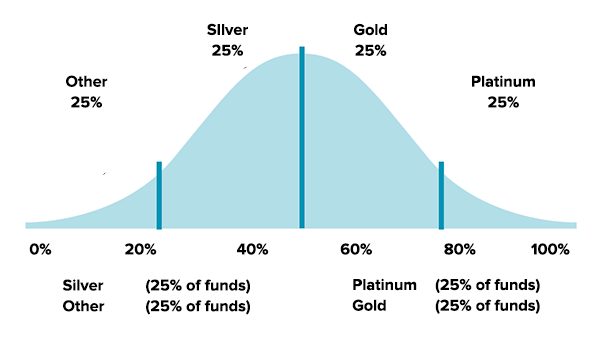

It’s from these payments that the potential conflicts arise. Ratings agencies know that funds who receive ‘poor’ ratings are less likely to pay for future ratings or other auxiliary services. This has led to a ratings system that has ultimately been designed to appease the funds rather than provide valuable information to investors. For instance, Super Ratings gives 25% of all funds a ‘Platinum’ rating, 25% ‘Gold’ and 25% ‘Silver’.

How many other competitions exist where a silver medal is awarded exclusively to competitors who have finished in the bottom half?

Source: SuperRatings – Methodology Info Sheet

Maybe awarding 75% of funds ‘silver or better’ would be fair if 75% were actually performing well. But as we found in our Fat Cat Funds Report, the majority of funds lag the market performance after fees.

So giving 75% of funds a Platinum, Gold or Silver badge seems at least a little misleading to consumers who are trying to select funds with above-average performance.

But what about the really stinky funds? The ones that are later likened to ‘Ponzi schemes’ like Trio/Astarra. Surely the ratings agencies are diligently identifying their poor governance, unusual structuring and risk-system red flags during their thorough analysis?

Unfortunately for investors, “the money poured in as Morningstar kindly bestowed its four-star product rating, and assorted financial planners dumped their clients’ savings into Trio for hefty commissions.” This wasn’t a unique case. A string of other collapses including Timbercorp, Westpoint and Basis Capital were also highly rated.

The best explanation of why the majority funds get good ratings probably comes from Warren Buffett’s long-time business partner Charlie Munger, who once said; “Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome”

It’s clear that the descriptors given as fund ratings are pretty unhelpful to investors. But what about relative rankings? Even if there are too many ‘higher-rated’ funds, surely these still outperform the ‘lower-rated’ funds?

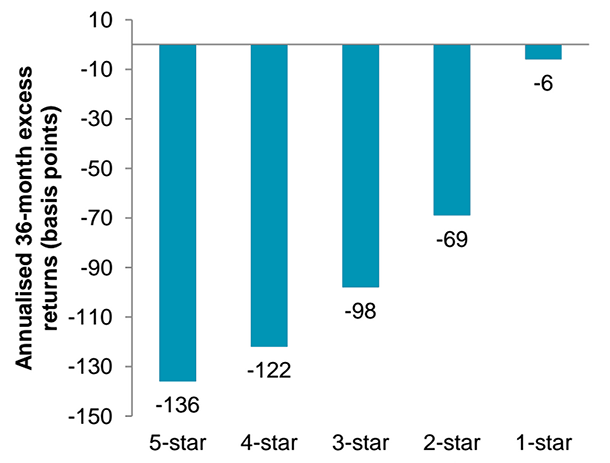

Vanguard recently addressed this question in a research paper. They looked at fund performance for the 36 months after funds received a rating from Morningstar. Their surprising discovery was that the highest 5-star funds actually under-performed the lowly rated 1-star funds by about 1.30%.

Sources: Vanguard calculations using data provided by Morningstar, as at Dec 2012.

That’s right, by investing in the worst 1-star funds you would have actually beaten those who invested in 5-star funds. In fact there was almost a perfect inverse relationship between ratings and future fund performance.

Why does this happen?

There are probably a few reasons but the most likely explanation is the ‘mean reversion’ of fund manager performance over time.

Ratings agencies tend to put a lot of weight on recent fund performance. However, fund managers who have performed well over the recent past often perform badly in subsequent years because investment styles are ‘mean reverting’.

For example, a ‘value’ fund that beats the market for a few years is prone to underperformance when ‘growth’ stocks excel for a few years. In the Fat Cat Funds Report we found very few managers who were able to consistently outperform the market, even over 5 years.

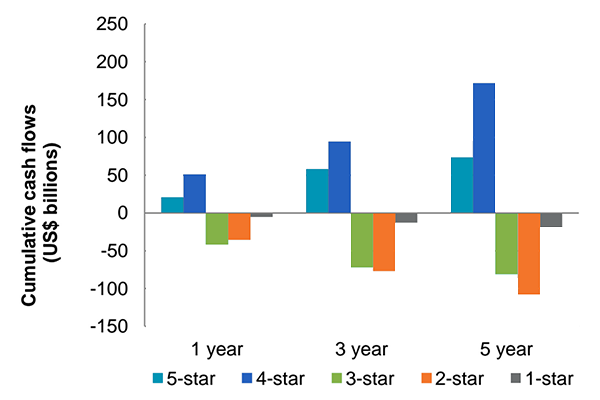

What makes this worse for investors is that the weight of money also follows recent performance so money tends to go exactly where it shouldn’t – into funds that have experienced recent luck which is likely to reverse.

Sources: Vanguard calculations using data provided by Morningstar, as at Dec 2012.

Of course there are a small number of managers out there who are able to consistently beat the market – but these are few and far between. In addition to being rare, it takes 22 years of performance data to have 90% confidence that their performance was actually due to skill and not luck.1

What can I use instead of ratings?

The answer is pretty simple. In Morningstar’s own research they discovered that fees alone were a better predictor of future returns than ratings. We demonstrated similar findings in our Fat Cat Funds Report where we found the strongest correlation existed between future returns and fund fees.

What it all means

Instead of relying on ratings agencies to determine what makes a good investment, we rely on our own research and evidence-based criteria to select investments. That goes a long way to explaining why our portfolios contain funds with low fees (a proven success factor), rather than ‘big-name’ 5-star funds.

Index funds and listed exchange traded funds (ETFs) have been the understated achievers when it comes to successful investing. They have consistently beaten the average ‘rated’ active fund manager for decades and we believe will continue to do so since generating alpha (excess returns above the market return) remains highly competitive in Australia.

If ratings agencies were concerned about substance, they would tailor their ratings to how investors actually use them — as an indicator of a good investment. If they did that, the majority of 5-star or Platinum rated funds would just be index funds. Unfortunately this is unlikely to happen while ratings agencies have an incentive to satisfy the funds that they rate.

Which begs the question, should the investment industry even be allowed to use ratings to entice consumers into their products when ratings agencies themselves admit that their scores contain limited information value?

Find out how Stockspot makes it easy to grow your wealth and invest in your future.