There have been a few books and documentaries that have tried to capture the Global Financial Crisis but probably none more entertaining than The Big Short.

For those who haven’t read (or seen) it, The Big Short is the story of a few eccentric traders who anticipated the US housing bubble and worked out a way to profit from it.

The book was written by Michael Lewis who you may recognise from some other top-sellers like Moneyball and The Blind Side. Before those two, he also wrote ‘Liar’s Poker’ in 1989 which was a semi-autobiographical memoir about his time on the bond trading floors of the late 1980s.

Fittingly, The Big Short continues where Liar’s poker left off – at the peak of the US housing bubble which owes much of its existence to the junk-bond days of the 80s.

Having enjoyed the book a few years ago, I saw the film last week and it once again made me reflect on my own experiences in 2008.

My professional funds management career began at the start of the financial crisis. I landed my dream job at the in 2007 at UBS Investment Bank, working as a trader in their internal proprietary investment team. Similar to Steve Carell’s team in The Big Short, our job was to make money for the bank by trading shares and other securities.

We could bet on positive or negative outcomes (known as ‘long’ or ‘short’) and the strategies incorporated complex instruments that most people would never invest in – convertible bonds, credit default swaps (CDS) & exotic equity derivatives to name a few.

I arrived in London for training on September 15th 2008 – the day Lehmans filed for bankruptcy. That morning everyone on the course was told that the planned presenters from the bank had to pull out last-minute. The news didn’t get better as the next day we found out many of us wouldn’t have jobs when we returned to our desks.

I landed back home in October 2008 at the depths of the crisis. Banks in Australia, Europe and the US were barely surviving day-to-day and staff were being laid-off in the thousands. The Swiss government had just announced a $60 billion bailout package to keep the 150-year old UBS alive. My team had halved in headcount while I was away for those few weeks.

Source: The Financial Times

By sheer luck I kept my position in the bank and was fortunate enough to spend 4 years learning from a brilliant team of traders. Over those years, many of our trading decisions were shaped by the financial crisis and government response that followed.

For me, The Big Short highlights 5 important investment lessons anyone can learn from the financial crisis and the protagonists who profited from it.

1. Just because everyone believes it, doesn’t make it so

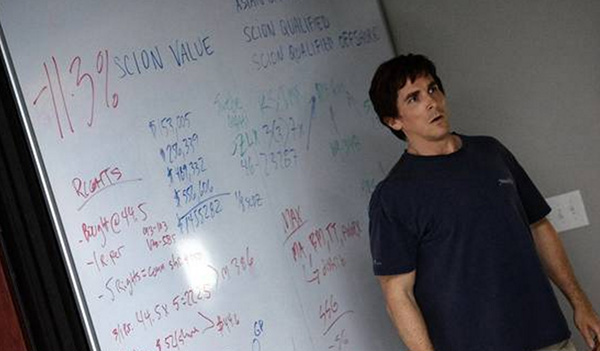

Michael Bury (played by Christian Bale) is laughed at several times in the film when he suggests that US house prices could fall – let alone crash. That actually gave him more conviction that he was right.

Markets reach extremes when everyone has the same belief and market bubbles end when there are no more buyers left. Always be cautious about consensus-held views because they often mark turning points, not only in markets but in others parts of life too (fashion, music etc)

The most successful investors, designers and musicians have usually been contrarian and acted counter to the commonly-held view. But as you’ll see, timing of when to bet against the crowd is crucial…

2. The market can stay irrational longer than you can keep your job

I first heard this investment adage from my university finance professor and the film demonstrates it perfectly. Regardless of how certain you are about an investment, the market can be wrong for longer than you can hold your position or keep your job.

In the film, both Burey (Bale) and Baum (Carell) are almost forced to exit the trades that eventually made them billions because those trades initially lost them money. Between 2005 and 2007, Bury lost tens of millions and was fortunate he was able to ‘put the gates up’ on his fund so investors couldn’t leave.

Markets can be irrational for longer than you may expect so it’s important no single holding is too large a part of your portfolio and ensure you can meet any short-term cash-flow needs in the meantime. That’s why we recommend that all Stockspot clients keep 6 months’ worth of savings in cash or short term deposits before investing.

It’s also why we don’t allow leverage or margin loans with our strategies because that increases the risk of being forced to exit a good long-term portfolio if markets are irrational over shorter periods and you can’t put-up the required margin.

3. Don’t fall for the hot hand fallacy and chase returns

The ‘hot hand fallacy’ is the flawed belief that a person who has had success with a random event has a greater chance of further success in additional attempts. The term comes from basketball where commentators often describe players as being on a ‘streak’ with their shooting.

In 1985, a psychologist and mathematician team disproved this theory that recent shooting success predicts success in subsequent shots. They found that each shot was completely independent, and that people have an inability to understand and accept randomness.

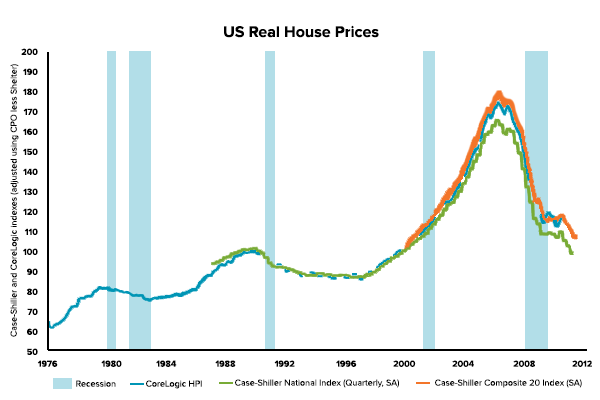

In the film it’s shown that bets on US house prices kept increasing as prices rose in the belief that house prices were on a ‘hot streak’ and would never fall. This eventually magnified the impact of the housing crash. House prices in the US fell by an average of 33.8% from peak to trough.

Over the long-term, assets have always reverted back to their long-term averages so following a period of strong returns you can usually expect a period of poor performance. This is why when we rebalance our client portfolios, we’re typically selling those assets which have performed well recently and re-investing in those which have underperformed.

Over history this has proven to be the most vigilant way to keep risk under control and avoid chasing momentum which is just like falling for the ‘hot hand fallacy’.

4. Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome

In the film we see how mortgage brokers and ratings agencies were influenced by financial incentives. As a result they weren’t conducting appropriate risk-checks on borrowers or giving fair or accurate ratings to risky packages of mortgage bonds. Financial conflicts was arguably one of the main reasons that the dangers of the US mortgage market went unnoticed for so long.

The best explanation for why even the stinkiest of mortgages kept getting good ratings comes from Warren Buffett’s long-time business partner Charlie Munger, who once said of financial conflicts of interests; “Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome”.

Ratings agencies around the world continue to get paid by funds and investments they are rating, which is why we believe they add very little value.

The best way to create good outcomes is by aligning incentives. This is the reason Stockspot doesn’t charge for brokerage as that would lead to a distorted incentive to over-trade rather than invest for the long-term, which is in the best interest of our clients.

Most of the financial planning scandals of recent years could have been avoided with better aligned incentives. As ASIC Chairman Greg Medcraft said recently, ‘robo advice’ has the potential to remove many of the conflicts of interest which have led to consumer losses and poor financial planning practices.

5. Be conscious of counterparty risk

When you invest you always have some level of market risk. But sometimes you also have other risks that are less obvious, more dangerous and ones that you’re not getting compensated for.

In the film, both Baum (Carell) and young investors Geller (Magaro) and Shipley (Wittrock) realise they face a different risk altogether – counterparty risk. This is the risk that the other ‘party’ to their investments may not be good for them when it comes time to pay out.

Since the very banks that they made trades against were at risk at becoming insolvent, the film protagonists had to work out how to cash out of their successful trades before they became “too successful” and bankrupted the banks they bet against.

Having worked at a bank during the financial crisis, I saw first-hand the importance of mitigating counterparty risk. It’s something we take very seriously at Stockspot and the reason why all assets are held beneficially and legally by our clients rather than using a trustee or custodian which exposes clients to counterparty risk.

There are too many examples even in Australia of clients losing money due to counterparty risk – MF Global, Storm Financial and Opus Prime just to name three.

Stockspot and our partner businesses never have any right to take custody or ownership of our client assets and I believe this is the best protection that exists to prevent misappropriation of assets. From what I’ve seen, many other automated investment service or ‘robo advice’ business don’t currently ensure the security of their client’s assets in this way.

Before you invest, always be on the look-out for words like ‘custodian’, ‘trustee’, ‘house account’, ‘pooled account’ or ‘fractional units’ in the product documentation. These all signal that you’re putting your trust in another business to hold onto your investments.

The reasonable ‘compensation’ for this additional type of risk is around 1% per year, reflecting the 1-in-100 chance that the counterparty goes bust and you lose everything.

It happens more often than you may think. But most likely you’ll be taking that extra risk without getting compensated for it at all. That’s a potential ticking time-bomb you shouldn’t need to hold.

Find out how Stockspot makes it easy to grow your wealth and invest in your future.