It’s confession season for Australia’s largest active fund managers.

Each year around this time, letters land in inboxes explaining why they did (or didn’t) beat the market. And once again, the themes are predictable.

Those who outperformed are patting themselves on the back for their “brave calls” on Nvidia, Telstra or some other sector that happened to boom. Those who underperformed are lamenting their underweight positions in the same areas, or their reluctance to own too much Commonwealth Bank.

It makes for entertaining reading, but what stands out most is the lack of self-awareness.

Active managers are smart people. They usually graduated top of their class, studied finance or economics, and fought off hundreds of others to land a coveted funds management job. Yet most still miss a simple truth about the industry they work in.

Investing is a zero-sum game. For every manager who beats the market each year, another must underperform. In aggregate, active managers are the market.

This creates what’s known as the “paradox of skill”. When everyone is highly skilled and has access to the same research, the same analysts, and the same technology, luck becomes the main factor separating winners from losers. Most of this year’s underperformers aren’t less talented. They were simply unlucky to be on the wrong side of a bet someone else got right.

Blaming the index

In the past few weeks, I’ve read countless fund managers justifying why they’ve been underweight Commonwealth Bank. Many still insist they’re “right” and the market is wrong. At the same time, some of these managers take pot shots at index investing, claiming it forces investors to buy “too much” of overvalued companies and “too little” of undervalued ones.

It’s easy to blame the index when things go wrong. But this is the wrong lesson.

The real issue isn’t that indices are flawed. It’s that almost no active managers have the skill to reliably determine what’s undervalued and what’s overvalued.

When every other fund manager has access to the same information, the same analysts, and the same technology, there’s no sustainable edge anymore. Which is exactly why, year after year, simple low-cost portfolios of ETFs outperform most so-called sophisticated investors.

The active manager’s conundrum

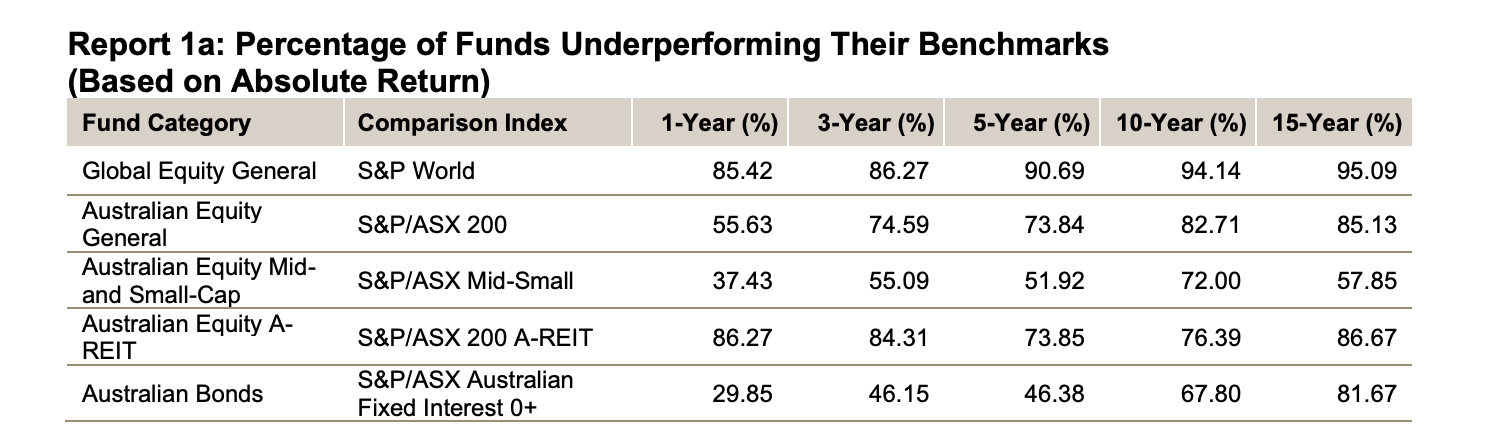

And it’s not just in rising markets that active managers have fallen short. In periods of market stress- the tech wreck, the GFC, COVID, or the recent rate hikes- most active managers still underperform.

They give up diversification in the hope of higher returns. But that concentration usually just increases risk. S&P calls this the “active manager’s conundrum”. The conditions they need to outperform – low volatility, high dispersion and high correlations – rarely happen at the same time.

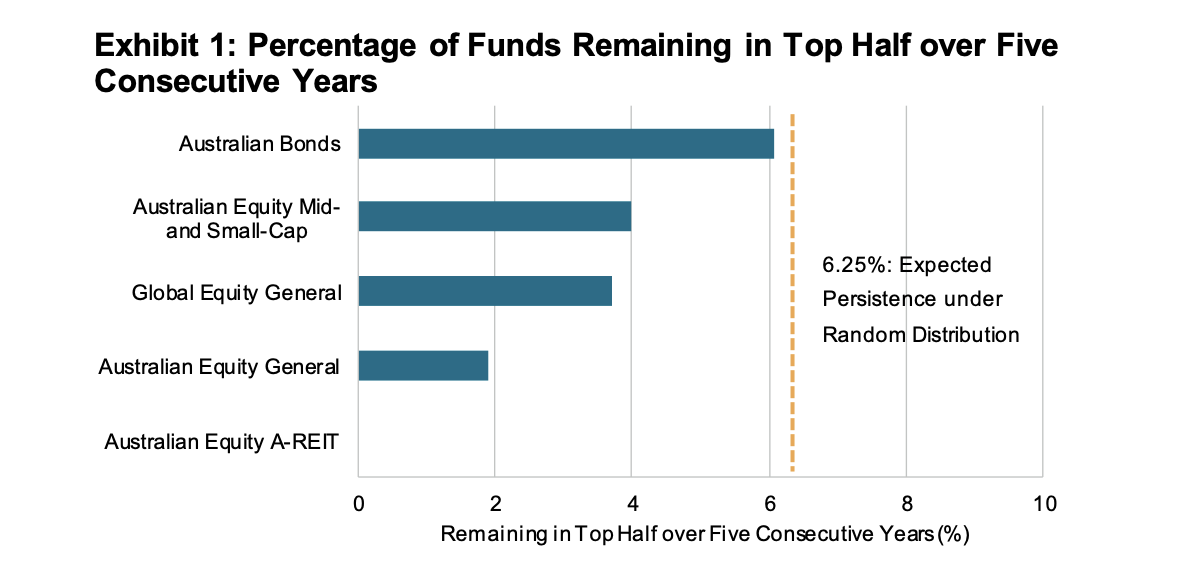

The persistence problem

Even the few who outperform don’t stay ahead for long. S&P’s SPIVA persistence scorecard shows just how fleeting outperformance really is. Out of 195 top-quartile Australian share funds from 2022, just three (2%) remained in the top quartile for each of the next two years, compared to an expected 6.25% under random chance.

illustrative purposes. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

And even if you somehow pick that 2% before they’re proven, there’s no guarantee they’ll stay there. Platinum, Magellan, Perpetual – they all had their moment in the sun, only to fade as assets ballooned, incentives shifted and performance fell away.

Meanwhile, the long-term numbers are brutal. Over the fifteen years to the end of 2024, fewer than 15% of active funds outperformed. Fees, taxes, transaction costs and franking leakage make it almost impossible to keep pace with the market over time.

It’s no surprise some large super funds are finally waking up and rethinking whether member money should be gambled on guessing if bank shares are over or underpriced.

Chasing the wrong things

Yet despite this, many big super funds are still pouring money into external active managers, private credit, venture capital and other fashionable alternatives to try to beat each other. They chase complexity while ignoring simple, transparent strategies that work.

Take gold, for example. Over the past year it’s been one of the best-performing assets, up 42%. But most super funds missed that return entirely because they were too busy trying to justify opaque high-fee alternatives.

It begs the question – why are super funds spending billions each year on active managers and asset consultants when a low-cost indexed strategy consistently delivers better results?

The simple truth

The answer is uncomfortable for the industry but clear for investors.

You don’t need heroic calls on Nvidia or Commonwealth Bank. You don’t need to take billion-dollar gambles on startups. You don’t need to try to out-guess other highly skilled players in a zero-sum game.

The best investment results go to those who stay diversified, keep costs low and stay invested, not those who try to outsmart a market full of equally smart people.